Gianpiero Petriglieri, INSEAD

Annotated remarks for the ‘Evidence-Based Leadership Development’ symposium at the 2022 Academy of Management Annual Meeting.

Before I speak about my principles I need to start with a preamble. The intent of all my work is to humanize leadership and its development, to make it account for emotions and relations and all the messy stuff that makes us whole and can break us apart. And I believe that the way to start doing that is to take seriously the idea that leadership is an art.

Leadership is an art like other arts. It involves bringing an idea to life, giving it shape, inviting others to gather around it. Like any other art, leadership can be controversial and consequential. It can be niche or pop, good or bad, but it is necessary—for the same reason that all art is necessary. Because there is uncertainty, suffering, fragmentation, and we are going to die—even if we don’t like to think about it. But we are here for now, we have this gift called life, and we are looking for meaning, direction, and connection to live it well.

We’re looking to be held and to be moved.

That is what art does. It holds and it moves us. Not everyone maybe, but enough people. (What is art for me might be rubbish for you). And that is what leadership must do too. It is not just a tool, a set of skills, to get stuff done. It is an expression of our wish to live well.

The psychological work of any art is to express a longing and to evoke freedom. The social work of art is to have an argument with tradition. Art often challenges a tradition to renew it. And to do that an artist, like a leader, must be committed but not captive to the tradition.

Some take this preamble to mean that leadership is not a science. Nothing could be further from the truth. If you read it that way, you do not get how much science, how much scientific work there is behind any art, be it painting, cooking, sculpting, ballet, or leadership. Every art requires discipline and skilful performance. But that is not enough. The discipline, the science, the skill, must be put in the service of an intent that makes the performance meaningful, an intent that is both deeply personal and yet not just about you.

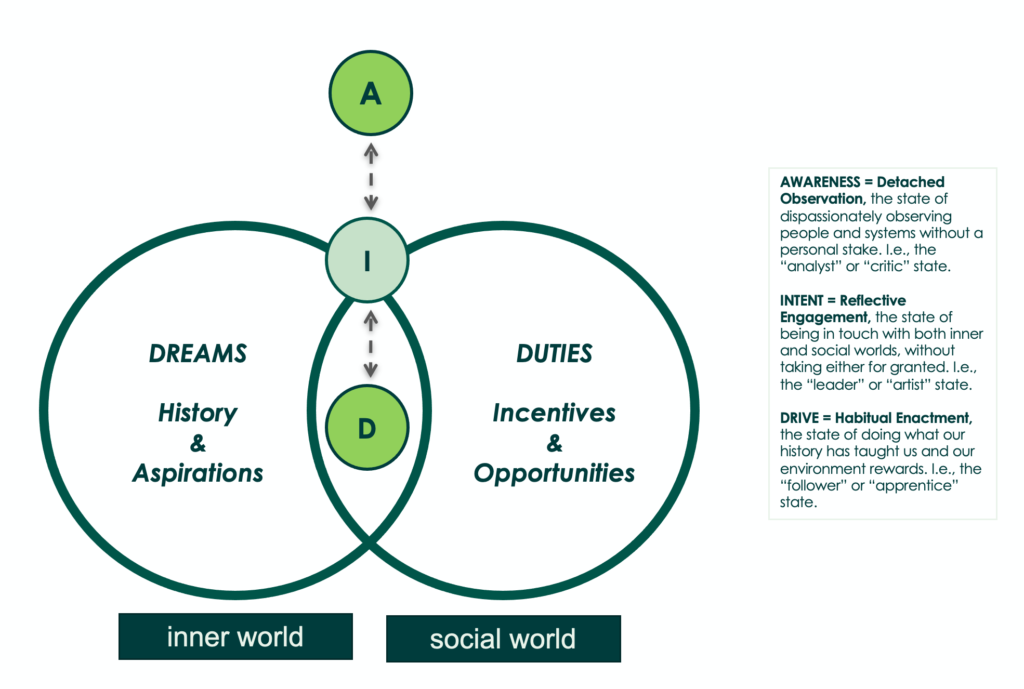

That said, here is my basic principle. Leadership development must provide the space to clarify one’s intent, and the resources to commit to it and bring it to life. Let me put it in one picture. From a systems psychodynamic perspective, which is the intellectual tradition that my work builds upon, each one of us, every single day, must deal with two worlds, two very real worlds. Our inner world, the world made of histories and aspirations that shape our dreams. And our social world, the incentives and opportunities that shape our duties.

Most of our time we spend in a state of drive, proving that we can be who we’ve learned to be and who we are expected to be, compelled to repeat our habits and fit our institutions. In this state, we make great apprentices, we replicate the masters. On occasion, we go up there, in a state of awareness, and we turn into critics. We meditate on our worlds, we study them, we critique them, and then we get sucked right back down into our drive. What I am interested in is this space in the middle, this state of intent, in which we are in touch with our inner and social world but not in the grip of either. That’s where leadership begins.

We are working with intent when, like an artist, we are committed but not captive to the traditions that shape us. Therefore, I believe the most important question any aspiring leader can ask is: am I using my energy, my skill, to indulge my drive or honour my intent?

It is difficult to get to or stick with intent for long on our own. It takes some resources, and for leaders those resources are other people who commit to sustaining our intent, rather than rewarding our drive. Hence leadership development work, of any kind, must help those who engage in it build relationships that sustain their intent. At its best, it must create communities where a plurality of identities and intents does not lead to polarization.

How do my colleagues and I do that in practice? We use the same methods everyone else uses, really, organized in a flow that follows the blueprint of the ‘hero’s journey’, a pattern of development. There is a preparation stage, an orientation that is mostly intellectual, a series of experiential activities with assisted reflection, and then a moment of integration where insights and questions can be brought back into one’s everyday life and work.

Since I only have few minutes, however, I do not want to speak about methods, because I believe what makes any development work effective is not the methods. It’s the people. We teach managers that leadership is all about the people, but when it comes to us, we focus on methods instead. The title of this panel is ‘walking the talk.’ But methods don’t walk or talk. People do. Or Moore precisely, professionals do.

One of the things I have spent much of my life doing, that I am proudest of, is helping to develop a community who brings this work to life. And that includes selecting professionals from a variety of backgrounds, training them, gathering them, committing to personal and group development, and then doing the same work that we ask participants to do. When executives ask me what is unique about the leadership development work I do, I show a slide with pictures of my colleagues in the work. What is unique? It’s not it. It’s us. It may not be what they expect to hear, but it’s the truth.

The last point we were asked to speak about has to do with assessment. I am delighted that, as a field, we are moving towards the idea that there is not one leadership development, but a multiplicity of development paths. In a 2018 study in ASQ, Jen Petriglieri, Jack Wood and I found that participants used the same leadership development offering in different ways depending on their needs and aspirations and had different ways to assess its value. Some saw it as successful if it made them more flexible, others if it made them more resolute. Annie Peshkam and I recently published a study in AMJ showing that those who design leadership development in organizations also have different views about what it means and what should it do, and as a result, of what evidence signals its effectiveness.

One view, which we called the custodian view, is that leadership development must help align people to the organization and close some gap, hence the relevant measures are behavioural changes and retention. The second view, the connector view, is that leadership development must broaden inclusion, hence assessment involves finding evidence of that. And the challenger view is that leadership development must empower people to defy the status quo, hence measures of well-being, creativity, and engagement are most significant. These views reflect the three traditions of inquiry in organization studies, the positivist, the interpretive, and the critical traditions, and I believe that giving them equal space in our conceptualization, practice, and assessment of leadership development is essential.

It is essential to humanize leadership and counter the intoxications with individualism and instrumentality that risk turning scientific leadership into a 21st century version of scientific management, an ideology that worshipped the means and conveniently ignored the ends. We can do more than that, and we must do better than that. And allowing for a plurality of meanings and outcomes of leadership development is the way to do more and do better. It is the way put all our science behind the art of developing and practicing good leadership.

If you have any questions: gianpiero.petriglieri@insead.edu

For examples of how my colleagues and I apply this approach to an MBA class or to executive education workshops, check out the ‘teaching‘ page.